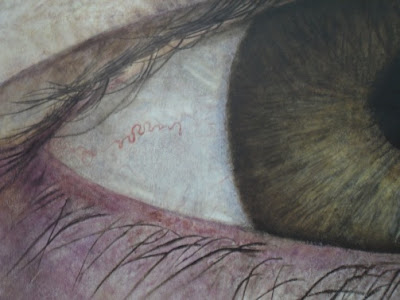

Detail of 'Face X', painting by Michael Roberts, copyright Michael Roberts 2010. All photographs this page by Margaret Sharrow, 2011.

Imaging the Face

PhD exhibition

Aberystwyth University School of Art Gallery

29 November - 28 January

Larger and closer than life, a series of faces loom up to the imaginary windows of a short series of canvases. This is 'Imaging the Face' by Michael Roberts, a select study of a few persons rendered in such detail and yet in a way that would make it difficult to identify them, even if they were known personally to the viewer. Roberts has been exploring this theme since his MA, slowly producing a series of paintings all titled Face and differentiated by Roman numerals. The most recent work, Face X took 18 months to complete, between 2009 and 2010.

Roberts, who describes his oeuvre as 'hyperrealist representation of the human face', has an almost scientific procedure he follows as a working method, appropriate enough for one who always works dressed in an immaculately clean white laboratory coat. The paintings originate from one digital photo, which is drawn on canvas. Roberts then reshoots details of key elements of the face using macro photography at a scale of 1:1 to 1:6, which are then the basis for painting. For Face X, he further used microscopic photography to a magnification of between twenty and four hundred times life size. This third layer of photography was presumably also taken directly from the face, rather than enlarging the first photograph. The notes on the exhibition panel suggest that details such as translucent hairs may be lit differently at different times.

It is inevitable that the work will be compared with other photorealist painters such as Chuck Close. However, while Close's famous hyper-enlargements of the 1970's were larger than most photographic reproduction technology could produce at the time, Roberts is working at a time when the only limits on printing size seem to be the width of the paper roll. Roberts emphasises the 'handmade' quality of his images, produced over the course of months, the opposite of speedy digital printing. Close's work also mimicked the limitations of the camera, particularly that of depth of field, so that features of his sitter's faces are 'in focus' while hair and clothing slightly further back in the picture plane are blurred. Roberts, in contrast, has invested features in different parts of the picture plane with equal levels of detail, detail beyond the level that could be achieved by a single photographic image encompassing the entire face. In assembling details from a mosaic of microphotographs, he has actually flattened the perspective of the face. While wide angle lenses emphasise the distance between close and distant objects, zoom lenses compress that apparent distance, making a row of buildings on a street appear to pile on top of each other. Macro lenses are essentially zoom lenses, and so a series of details of a nose shot with extreme, even mircroscopic macro lenses, when set side by side will make the nose appear more flattened against the face than we are used to, our 'normal' naked eye vision being equivalent to a 55mm camera lens, and most portrait photography shot around a familiar 80mm.

The effect of the flattening, combined with the close cropping removing all hairstyles, clothing and other signifiers of gender, social status, etc. is disconcerting. As is the detailed rendering of blemishes, bloodshot eyes, moles, even fine hairs we don't normally see. The effect is rather like staring into a magnifier makeup mirror my grandmother used to have: it had a set of glamourous lights down both sides, which could be set to 'evening' or 'day', in which case a ghoulish fluorescent green light illuminated every pore to garish proportions. Roberts is forcing us to confront the aspects of skin that we dwell on obsessively in the mirror, when it is our own skin, and yet that we politely ignore or recoil from in others. He has crafted images that are the opposite of those in Photoshop-filtered glossy magazines. The obsessive attention to detail, ironically bringing beauty to overlooked and sometimes (to put it bluntly) repulsive minutiae, is at its best when Roberts lets go a little, leaving the paint to make its own contribution to the rich texture of the human surface.

Installation views and details of paintings from the exhibition, below.

No comments:

Post a Comment